Why Are So Many Queer Characters Straight?

Short answer: capitalism.

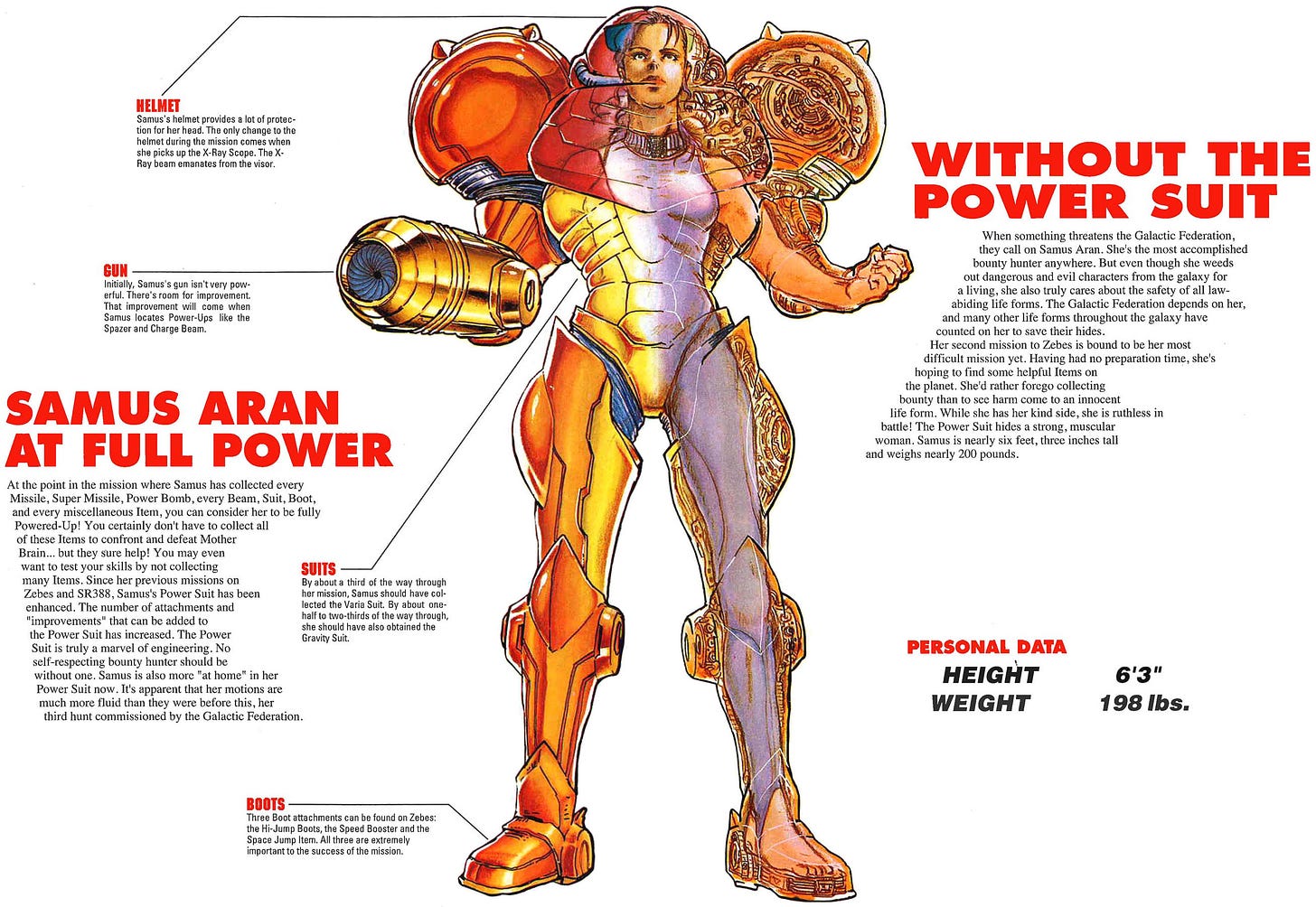

In a 1994 interview Hirofumi Matsuoka, a designer on the video game Super Metroid, made a transphobic joke about Samus Aran, the game’s protagonist. He claimed that only he knew the truth about Samus, she “wasn’t a woman,” but instead, “ニューハーフ,” or “newhalf.” The Japanese equivalent of the transphobic slur “shemale”. Instead of being outraged by this, the trans community grasped onto this joke and took Samus in. Many trans women look up to her: 6 foot 3 inches, 198 pounds, and long blond hair. She can rock heels or an armored suit and kick ass in both. She communicated to us that we could be beautiful, we could be powerful, and we could be both at the same time.

According to a 2021 GLAAD study, there were no transgender characters in any major studio film in 2020, and GLAAD states that trans representation in tv has fallen year-over-year to a low of 8 percent, or twenty-nine out of 360 total LGBTQ television characters in the report. studies show that these representations of trans identity lean into harmful stereotypes, “The most common profession transgender characters were depicted as having was that of sex workers, which a fifth of all characters were depicted as” and “Anti-transgender slurs, language, and dialogue was present in at least 61% of cataloged episodes and storylines”.

In the case of Samus, Nintendo has actively worked to backtrack on the idea of a trans Samus. As this fan theory has gained popularity, the company has slowly portrayed the character as smaller and slimmer in an attempt to distance her from potentially trans features, as well as publicly rebutting the original interview. Modern material from Nintendo says she is five foot two inches as of 2010.

Stories like Samus’s show the stigma that queer identities face in media, and it isn’t just a problem for transgender characters. A lack of queer representation communicates to the LGBTQ+ community, especially children coming to terms with their identity, that they are abnormal, and reinforces this to their straight counterparts.

There are numerous articles around the internet from queer people about their experience with finding stories that spoke to them. Harvey Fierstein in the documentary “The Celluloid Closet” recounts his experience growing up trying to find himself, “Readings in school were heterosexual. Every movie I saw was heterosexual. And I had to do this translation. I had to translate it to my life, rather than seeing my life.” When LGBTQ+ people can’t find themselves in art, they must make up queerness with what they already have.

GLAAD points out that seeing queer representation in the media can make a person about 20 percent more likely to accept queer people in their own life. The entertainment industry has always held a role in either upholding or tearing down social rules in public culture.

Putting queer characters on screen in roles that do not fall into harmful stereotypes helps normalize the queer experience to the public. Helping to fight against hate campaigns like the anti-trans bills seen in many state legislatures this year, or the concentrated effort to purge queer stories from school lessons.

For the longest time, the closest thing to queerness on screen was the long history of queer-coding characters in stories. Disney has a history of ‘queer coding’ its villains. A paper from the Journal “Discourse@RU” states “Television continues to queer code villains through stereotypical depictions of traits and behaviors to reinforce traditional gender roles and to equate deviancy with villainy.” Think of Scar, Hades, and Ursula. Effeminate male characters and a female villain based on a drag queen. The mannerisms all evoke stereotypes of queer culture. If queer youth see themselves as villains, it continues the cycle of internalized homophobia.

Some Disney properties attempt to feign interest in queer representation, overhyping and under-delivering. Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker touted that it would include an LGBTQ couple, leading fans to speculate it would be between two main characters, Finn and Poe, who had also been accepted by fans as a couple. Instead, this representation was an extremely brief kiss between two nameless women in the background of the scene. However, even small moments like these in recent films get cut out when released in countries like China or Russia so as not to anger the governments and potentially lose money.

2021 was the deadliest year on record for trans people. The U.S. is seeing a meteoric rise in state legislatures to strip trans people of rights such as medical care or the ability to compete in sports and even have gone as far as to silence the few trans lawmakers able to fight back. Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay Bill” silences queer experience, and schools nationwide are quietly removing queer books from libraries.

5.6 percent of all Americans identify as part of the LGBTQ community as of a recent Gallup poll. At some point, we must acknowledge that continuing to attempt to censor queer stories is just an attempt to stamp out the identity and lives of queer people. The claim of protecting children can only go so far, especially when queer youth are four times more likely to attempt suicide than straight individuals.

At the heart of this is a refusal from the business of entertainment to work towards equality for the LGBTQ+ community. Corporations like Disney will think of how they can appeal to the largest number of people to make the largest profit. At times this aligns with queer representation, but only on the surface, and in very small ways. But it always has a foot in the other camp, ready to delete a scene. It is one hand reaching out to claim allyship, while the other holds a knife in your back.

There are few queer characters for us to connect with, and what we do have is mired in stereotypes and corporate greed. We find our stories in the spaces between. And while companies and legislature actively work to erase any history we do have, the queer community always finds a way to live on.

I originally wrote this in the spring of 2022 for a grad school class but thought with the resurgence in the conversation over Samus’s identity and general conversations about representation in the time of active hate against the LGBTQ+ community, it would be a good time to post it. I did some very light editing so it might read as a little out of date, sue me.

Also, I didn’t post a weekly round-up last week because I was traveling for work (how jet set) but I will be back with one this weekend.